Five inconvenient truths about scrap (part 2)

For more information about WSD’s SDDS service or to request a sample report, https://www.worldsteeldynamics.com/services/steel-decarbonization-dynamics-service-sdds/

In a preceding article, I identified five inconvenient truths about scrap and their implications for steel industry decarbonization. Growing availability of obsolete scrap is the key enabler for industry decarbonization, but there are challenges regarding its practical accessibility, recovery costs, geographic distribution and quality that need to be addressed for the industry to maximize scrap’s decarbonization potential.

This article focuses on one of these truths: that rising copper contamination in scrap may reduce the amount of scrap available to the industry for decarbonization and/or dramatically increase the amount of capital needed for decarbonization. World Steel Dynamics recently completed an in-depth assessment of copper contamination in the U.S. scrap stream which forms the basis for this article.

Why worry about copper contamination in scrap?

Excessive levels of copper contamination in steel cause surface defects, “hot shortness”, and loss of ductility particularly for flat roll steels. This drives the need for strict monitoring of the copper levels in the scrap used in EAF steelmaking as well as for increased use of ore based metallics (OBMs) such as DRI. Once melted in with the steel, copper cannot be removed: it remains “contained” in the steel in final product (cars, appliances, machinery, etc.) and enters the scrap stream as these are recycled at the end of their useful lives.[1]

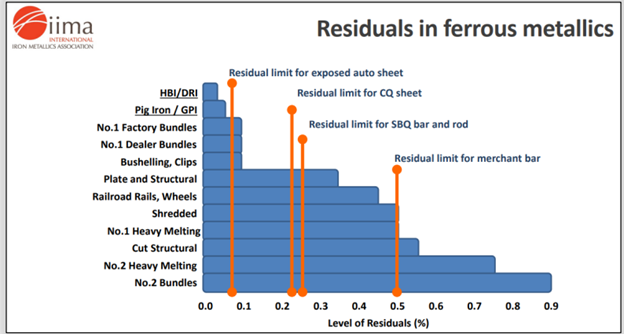

The following chart from the International Iron Metallics Association (IIMA) indicates the threshold for residuals (primarily copper) concentration levels for key steel products and the corresponding typical residuals concentration levels in the major scrap categories.[2]

As can be seen, “allowable” copper levels range from ~ 0.06% for exposed automotive sheet to 0.50% for merchant bar. Typical copper levels in scrap range from ~ 0.1% for prompt scrab grades to almost 1% for No.2 bundles. To be able to utilize scrap with higher copper levels than can be tolerated for a specific product, steelmakers need to dilute this scrap with lower copper containing prompt scrap, OBMs, or both.

How copper enters and can be removed from the scrap stream

New copper enters the scrap stream through the incomplete removal of copper containing components when final products reach the end-of-life (EOL) stage and are recycled. For autos, copper is used in radiators, small motors, wiring and other applications. Copper is used in buildings mainly for plumbing, HVAC systems and wiring. If not removed, this “free copper” becomes “contained copper” once the load of scrap is melted and the steel used to make a final product. Contained copper levels increase as more and more free copper enters the system over multiple cycles.

Copper-containing components can be removed at several stages along the scrap processing chain:

- when EOL final products such as cars are disassembled in conjunction with the removal of liquids, tires and resalable parts

- when buildings are demolished and the copper products are recovered and sold as copper scrap

- when the residual material after disassembly or demolition is processed at scrap yards

- during final sorting and extraction at the steel mill prior to melting.

Not all EOL copper enters the steel scrap stream: some is recovered in separate recycling streams as in the case of power lines, some goes into landfill as is often the case for small appliances. For copper that does enter the steel scrap stream the amount which is removed is strongly impacted by the prevailing market price for copper scrap.

Copper can also “exit” a domestic scrap stream when copper contamination levels in exported scrap are higher than that in scrap retained in the market. This situation prevails for much of the current scrap exports from the US and the EU.

Shredding which is the predominant method for processing EOL vehicles can make removal more difficult by embedding small chunks of copper in steel scrap (so called “meatballs”). The traditional method for removing copper elements is manual picking. The advent of more sophisticated shredding machines coupled with optical recognition and AI can minimize (but not eliminate) the amount of free copper that passes through.

Copper use is expected to grow at 3-4% per year due to strong growth in data center electricity demand, the number of EVs (which can contain up to 4 times the copper content as a comparable internal combustion engine vehicle), in the number of “smart buildings” and increased electrification of other products and services.

Current levels and base case forecast

World Steel Dynamics recently completed an in-depth assessment of copper contamination in the U.S. scrap stream using a conjoined material flow analysis for steel and copper use and EOL recovery starting in the 1950’s. We estimated the average current copper levels in obsolete in scrap and forecast potential future levels under different scenarios.

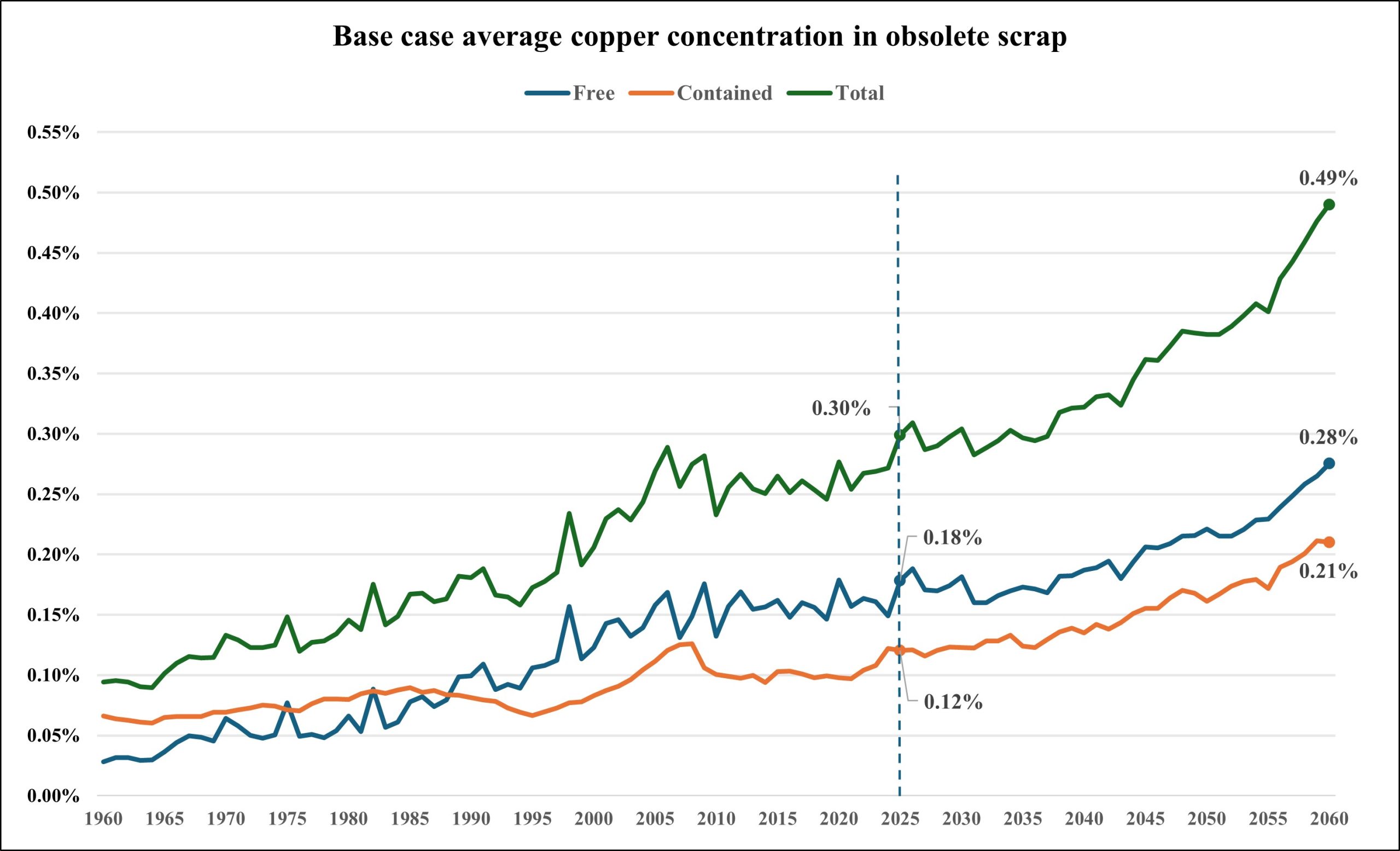

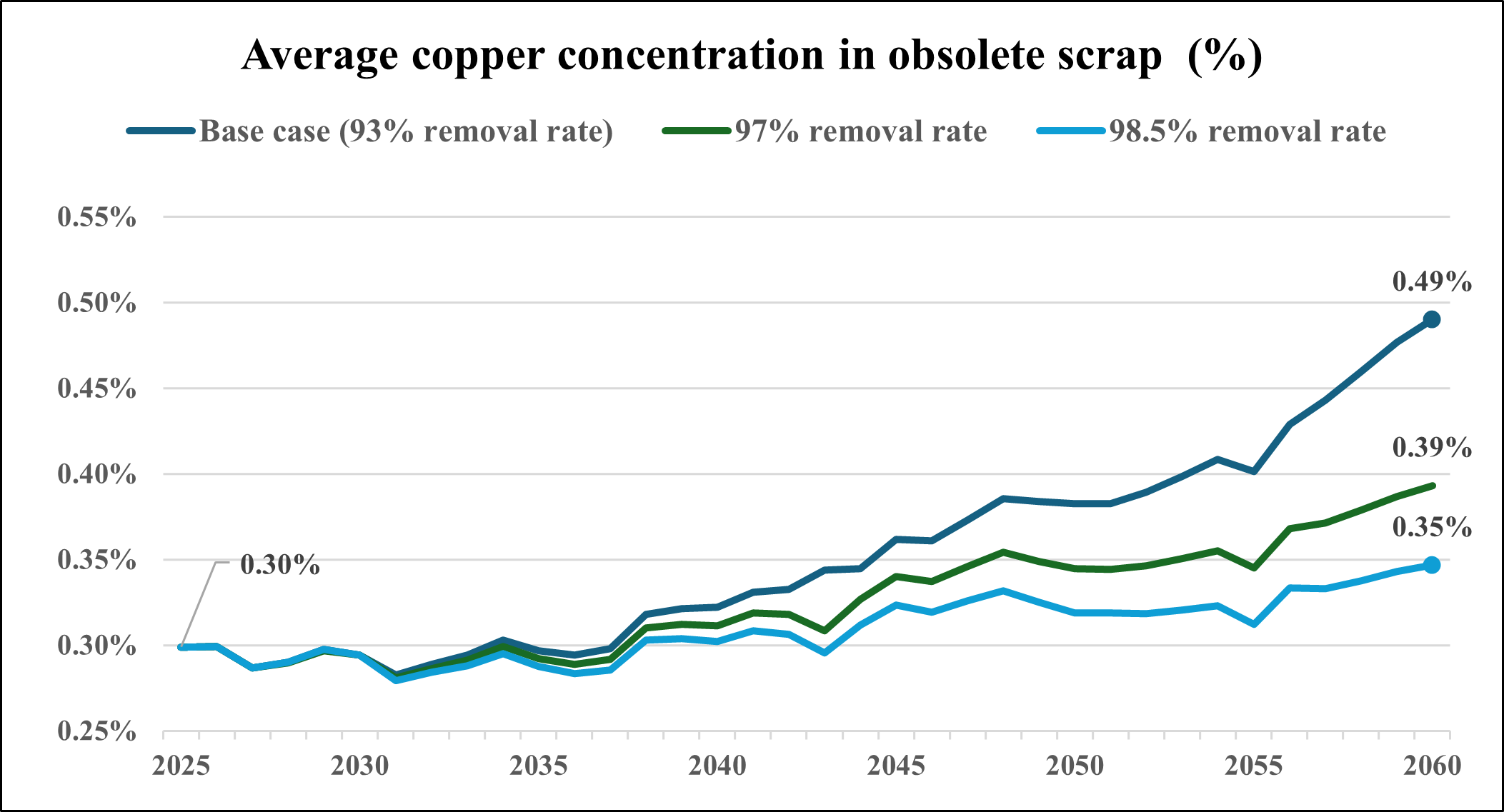

The base case scenario shown below assumes that 93% of the free copper potentially entering the scrap stream is removed by one or more of the methods identified above.

Copper contamination levels have been rising over the past decades. Current levels are estimated at ~0.12% for contained copper, ~ 0.18% for free copper and ~0.30% for total copper. These are average – some loads of obsolete scrap are higher, and some are lower. This current level of average obsolete scrap contamination is considered manageable based on:

- Reasonably efficient market allocation of high copper-bearing scrap at lower prices to the production of rebar, merchant bar or other copper -tolerant products

- Dilution in BOFs where scrap usually accounts for only 20% to 25% of the total charge

- Scrap exports as noted above

- Dilution in EAFs though mixture with low-copper level prompt scrap and/or DRI

- More rigorous detection and removal procedures during scrap yard and mill yard processing

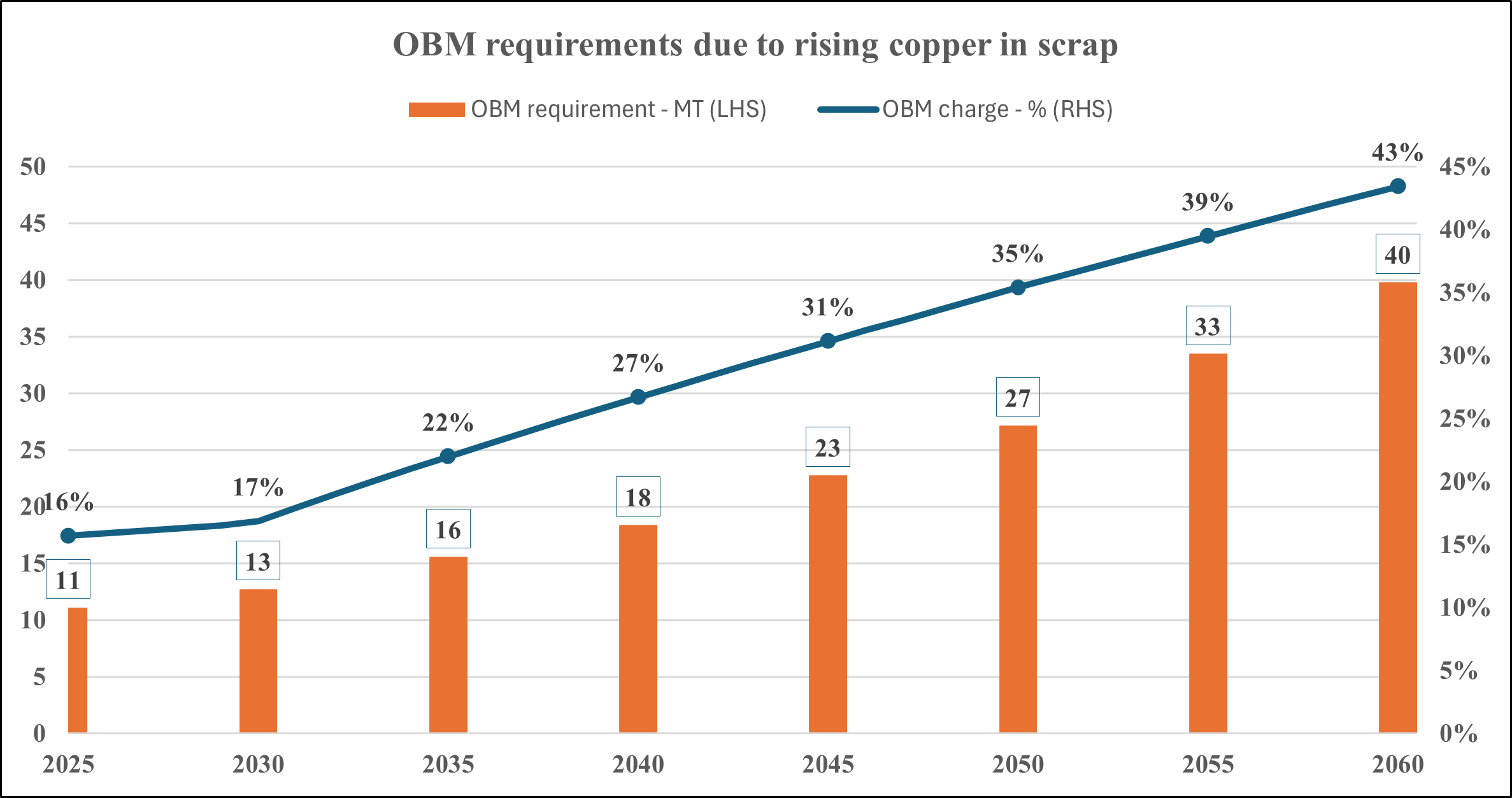

Based on the projected 3-4% CAGR growth in copper use and the 93% removal rate noted above, the average copper levels in the US obsolete scrap stream will increase and potentially reach 0.50% by the middle of the decade. Including the further assumption of the overall EAF production share increasing to >90% (compared to 72% in 2024) some level of dilution becomes necessary for essentially all steel products. The following chart shows that in the under base case assumptions, the average OBM charge would need to reach 43% and total DRI supply 40 million tons to keep within product specific limits.

Building 40 million metric tons of DRI capacity is entirely feasible, but the logistical and economic costs to achieve this are daunting. The US industry would have to expend $20-25 billion to install a new 2.5 MT DRI plant every 2-3 years to reach this level.[3]

Increased copper removal rate scenarios

The following chart shows how copper level growth would be slowed to more manageable levels (in terms of dilution requirement) if the average removal rate is increased from 93% to 97% or 98.5%.

The question is: can these removal rates be achieved?

There are no technical barriers to achieving these removal rates. Major scrap processors and some EAF flat roll producers using leading practices with advanced technologies, are already able to remove most free copper, achieving combed copper concentrations of less than 0.20%.

Instead, there are four main obstacles to increasing removal rates. The first is the absence of clear market signals based on copper level denominated scrap categories. Currently, lower copper level scrap garners a price premium, but this is based on individual scrap yard/mill negotiations on a load-by-load basis. Existing standard scrap grade specifications do not identify copper levels.

A second challenge which is closely tied to the first is that the business models of some scrap stream actors are not aligned with achieving system-side improvement. Because rebar or merchant bar producing steel mills do not require low copper scrap, the prices they are willing to pay do not justify the additional capital and/or operating costs the scrap yards would incur to remove the copper. The scrap yard may in fact be incentivized to leave copper components in loads in order to increase total weight.

The third challenge is insufficient awareness of the importance of the copper contamination issue. This includes in governments which can have an impact through recycling waste and other policies; in OEM car and other manufacturers by designing componentry for easier copper removal; and in scrap industry associations which expand education and training programs to include more on copper contamination and recovery.

The fourth and potentially most severe obstacle is the inherent time lag between removal rates today and the time in the future when the copper re-enters scrap stream as new free copper. The copper in an EV purchased will not re-emerge until the vehicle is scrapped ~ 15 years into the future. Copper-containing machinery may not be scrapped for 20-30 years, and copper in buildings longer than that. This explains why the projected copper levels shown in the first chart remain relatively flat until the middle of the next decade after which they accelerate.

Individual companies, especially EAF flat roll producers will continue to strive for higher removal rates as they optimize their raw material requirements. However, industry-wide action is required to address the systemic nature of the problem. Scrap streams are not closed loop systems around a specific steel product or sector. EOL auto bodies comprise only 25-40% of the material entering shredders which are the primary source for EAF flat roll production. White goods, machinery, construction residuals and other random EOL products comprise the balance. All scrap sources and all processing activities must be encompassed.

DRI capacity will need to increase even with increased removal rates. However, faced with the capital requirement of a greenfield DRI plant, the economics of investing in advanced scrap processing are likely to be more attractive in many situations.

Rising copper scrap prices due to a looming shortage of primary material will provide a strong tail wind for increased removal/recovery rates. But because copper levels are manageable today, the industry risks falling into a false sense of security. Unless efforts are made starting in the very near future, rising copper contamination levels will become a major constraint on steel industry decarbonization by mid-century if not sooner.

For more information about WSD’s SDDS service or to request a sample report, https://www.worldsteeldynamics.com/services/steel-decarbonization-dynamics-service-sdds/

[1] There are several research efforts seeking a cost and energy-efficient process to remove copper during steelmaking, but these are at very early stages with tremendous uncertainty as to whether their feasibility can be proven

[2] Jeremy Jones of CIX provided the chart and was a key contributor to the WSD study.

[3] The additional DRI capacity could either be built onshore or in another location.